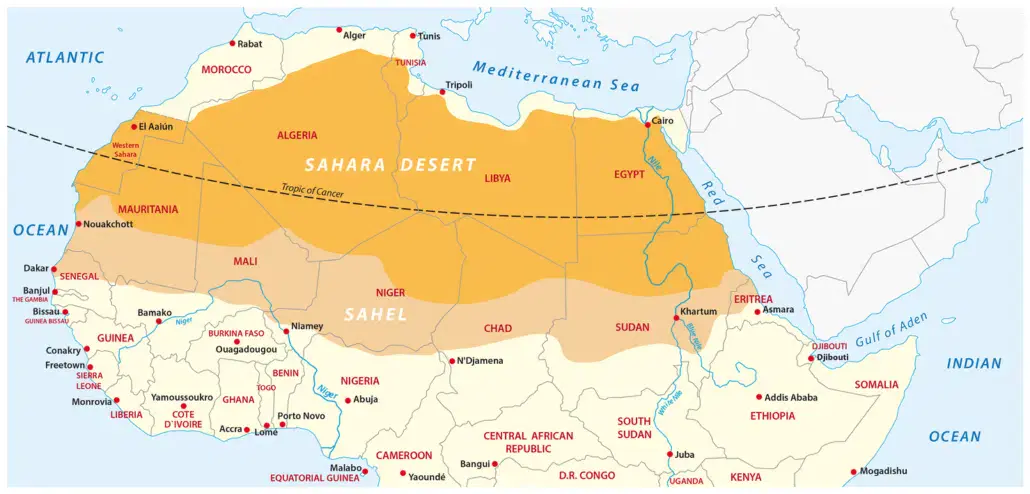

If the Sahel with its ten states between the Sahara and the Sudanese Savannah comes to mind, one thinks mainly about desertification. Understandably, the region is continuously threatened by increasing soil erosion.

However, a June report published by ACLED, a qualified source of political violence and protest* devotes itself to another issue: the ongoing conflicts with their huge dimension of humanitarian problems. 2021 marks the tenth anniversary of the Sahel crisis. Throughout that time conflicts were marred by brutality and violence of all armed groups, with massacres of civilians perpetrated by jihadists, who have been expanding and entrenching themselves. Once more it is the poor, who have suffered.

The report points out that though the crisis is transnational, the pattern of violence and change differs. It reviews three countries, Niger, Burkino Faso, Mali with an overall look at the Sahel. It discusses the Islamic State of Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the Al Queda-linked Al Islam Wal Muslimin (JNIM) which have moved “beyond the immediate reach of external forces”. By involvement in local conflicts, jihadist groups have expanded their influence. In 2021 the general humanitarian emergency increased, with JNIM trying to achieve compliance through violence. The crisis is bedevilled by local ceasefires, which are often broken.

Detailed accounts of fighting in 2020 and 2021 are outlined. This covers inter- jihadist conflict as ISGS and JNIM compete for local groups loyalties, their attacks on local communities to impose their control as well as massacres displacements, resistance by communities and reprisals. With a long history of ethnic conflict, criminal networks and strife between pastoralist communities, so that with new pressure ethnic fighting began to increase. That between Bambara and Fulani was one example, with a peace agreement breaking down in 2121. The Funali are seen as tied to ISGS in the three states, which by June 2021 bore 79% responsibility for civilian deaths. Militants from 2020 to June 2021 was estimated at over 1,400.

Following JNIM attacks of strategic targets and on the three-state forces, Niger armed its civilians (VDP) in 2018, These bore the brunt of fighting by 2021 in some areas. Critics feared their involvement would increase ethnic fighting, which was borne out this year.

France cooperated with state forces, leading to criticism of the French for misplaced airstrikes and because state forces abused human rights. President Macron threatened to withdraw after a second military coup in Mali in 2021 and withdrew temporarily. A 2020 major French operation in Mali, the epicentre of the Sahel crisis, temporarily weakened JNIM and ISGS, whose infighting died down as demarcation between them increased. Though JNIM attacked strategic targets in 2121, it also lost battles as Malian and French coordination improved.

State and French attacks concentrated on the border between Niger (faced with the Sahelian Boko Haram led by ISGS in the north, by JNIM in the southwest), Burkino Faso and Mali. The jihadists pushed southwest, regrouping to attack different communities which threatens Benin, where fighting between park rangers and JNIM-affiliated groups took place as far as 70 kilometres inside Benin. In Burkina Faso’s Southwest, jihadists seek to expand in the north of Ivory Coast, which experienced improvised explosive devices (IEDs) for the first time.

Burkina Faso had experienced a decline of deaths since a record high in March 2020. Last November JNIM enforced its order in the town Mansila, with the state only using troops when Sharia law was imposed. ISGS lost ground due to actions by French forces and G5 Sahel and its conflict with JNIM. This led to a shaky ceasefire which was often broken.

French and G5 Sahel forces focused on the tri-state border region, weakening jihadist groups, thus leading to their regrouping and fighting elsewhere. Jihadists also tried to expand in the north of the Ivory Coast. This year Ivory Coast experienced its first four improvised explosive devices (IEDs) attacks. The militants advance southward has continued and intensified with militant groups expanding their activities outside the border areas. Recently ISGS began amputating thieves’ hands.

Without a global effort, local agreements seem to be fragile. As the states drift away from the French-led alliance, JNIM and ISGS have expanded their influence.

Experts see the Sahel still in transition from feudal societies to national states, with strong institutions and visionary elites missing. The small elite which co-operates with the international community according to the South African Institute for Security Studies cannot solve the instability. Civil society organisations have called for some time for a shift from a military approach to addressing governance deficiencies and listening to the people to, involve them in decision-making. Such critics fear inequality and injustice leads to migration and upheaval.