Judges are more guilty than others, as they should have represented justice more justly.

Lothar Kreyssig

In September Germany‘s President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier received the historian Norbert Frei, whom he authorized in 2020 to investigate the post-war period of his office until 1994 and to report to him by 2022. It reminded me of the so-called “Zero hour in the years 1945 to 1949”, even if I only visited Germany for the first time in the 1950s – and hadn’t met a single Nazi! I wondered if the ghosts of that past were haunting our present, when hate, antisemitism, anti-Islamism, anti-humanity is part of daily life.

At the time Germans fervently wished to forget the past. The Third Reich’s collapse must have been a tough time for the enthusiastic majority, that had followed the national movement and accepted Nazi ideology, thus allowing the perpetration of incredible crimes. Their children were also not exactly eager to know precisely what had happened, leading to the “second guilt”, as Ralph Giordano had named it.

President Steinmeier‘s commission is part of a research series launched by Joschka Fischers in 2010 to look at the Foreign Affairs Ministry, the results of which caused deep dismay. Had a large number of post-war officials really been involved in the Nazi era? Unbelievable! But true. During the post-war years, Germans strenuously tried without a doubt to leave the immediate past behind them, as if it hadn’t happened. Chancellor Konrad Adenauer was aware of the people’s desire to draw a line beneath those 12 years. He admitted everyone had known about concentration camps – the KZs. How could they overlook it, in view of the 42 500 KZs, subcamps, ghettoes, worker- slave-labour- POW camps? It was inevitable that Germans passed at least one at some time if not daily – apart from the early years when rows of deportees were seen on the way to railway stations or later the death marches of KZ inmates back to the Reich. None were prepared to accept responsibility. The general view was that everything was in order, as it had been the law at the time. They had only followed orders. Others continued to march silently in the step they’d been taught. Had perhaps this been passed on within families and in private? Adenauer only asked that they kept a low profile.

The Allies arrested the leaders they could find so that by 1949 50 000 had been charged. Germans then took over, which meant that not even 1 000 were subsequently judged, though historians estimate some 500 000 had been involved in Nazi crimes. Of the 6 500 SS staff working in Auschwitz, merely 29 were charged in West Germany, 20 in the GDR. The Allies had instantly dismissed 65 000 civil servants. A large number was soon back in their posts. During the Adenauer era Nazis were re-inegrated. They avoided trials, received amnesties and were released from prisons. The explanation was that the civil service couldn’t function without experienced staff. The Ludwigsburg Central office to investigate Nazi crimes was established in 1958 without responsibility for war crimes so that the German defence force went scot-free. Ministries such as Foreign Affairs, Justice, Police were not the only ones with brown roots.

In 2012 the report on the Justice Ministry was issued. The question of judges interested me, as I had recently read a good deal about the courageous judge Lothar Kreyssig, the only one among the guardianship- and other judges, who had openly attacked the euthanasia programme, actually accusing its chief of murder. The notorious Judge Roland Freisler named judges as “soldiers of the law”. They had accepted the 1936 guidelines, which included Hitler’s decisions and utterance as law, thus abrogating their right to control the executive.

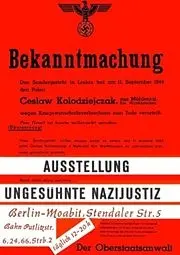

The Nuremberg trial of jurists of 1945/6 ended with four acquittals, four life imprisonment and other judgments of five to ten years imprisonment. All accused had been set free within ten years. Between 1959-1962 students of the Free University of Berlin mounted a poorly financed exhibition of documents concerning trials and death sentences, as well as details of the post-war careers of 100 Nazi judges and prosecutors. Despite efforts to prevent its showing and false charges of fake documents, the exhibition was effective. Charges were brought against 43 members of the Nazi Special Courts. In Hesse 159 were finally named. The number of former Nazi perpetrators increased: no judge of the Peoples or Special Court or any other Nazi Court was charged after 1945.*

Thousands of former NS-lawyers returned to serve the justice authorities so that their number actually exceeded that of 1933! Naturally, the younger generation had studied during the Nazi period. It is thus understandable that the research of the role of jurists was taboo during many post-war year decades. One example is the case against former SS jurists, namely former prosecutor Walter Huppenkothen and NS Judge Otto Thorbeck, because of the April 1945 trials against resistance fighters such as Hans von Dohnanyi, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Admiral Wilhelm Canari and others. These ended with death sentences, which were carried out weeks before the end of the war, with prisoners tortured, denied all aid and forced to walk naked to the gallows. This is considered one of the most crucial trials against former Nazi functionaries and kept several courts busy for six years.

The Munich Court confirmed 1951 the death sentences as justified for high treason. The Federal Supreme Court (FSC) overturned the judgment and returned the case to Munich, where a jury trial declared the sentences were justified, according to the law and judgments of the time. The FSC rescinded the judgment, but a Munich jury trial again acquitted the accused. On the 30. November the FSC overturned the judgment on appeal. In October 1955 an Augsburg Jury Trial sentenced Huppenkothen and Thorbeck for abetment to murder only to seven and six years imprisonment. The FSC partially overturned the abetment judgment, acquitting Thorbeck and sentencing Huppenkothen to six years in prison.

The FSC had thus changed its mind within a few years: understandable in 1956 when the judgment was given, 80% of the FSC had served in the Nazi judiciary. Nor did the Protestant Church object to this legitimisation of Rev. Donhöffer and other resistance fighters. As late as 1985 the German Parliament was unable to arrive at a resolution to overturn the judgment of the Peoples Court.

It was only in the late 1990s the FSC faced its history. Günter Hirsch, FSC chairman between 2000-2008 judged the opinion that the death sentences in the Huppen-kothen trial had been the correct trial procedure as “a slap in the face”, of which one had to be ashamed. At the centenary of Hans von Dohnanyi’s birthday in 2002, he spoke of the repression and failure to pursue Nazi crimes by the judiciary as “this failure of the post-war jurists” which had been “a dark chapter in the history of Germany’s judicial history and will remain as such.”

Hence my question: have the ghosts of the past been awakened?

* Stephan Alexander Glienke, Der Dolch unter der Richterrobe 1.12.2012